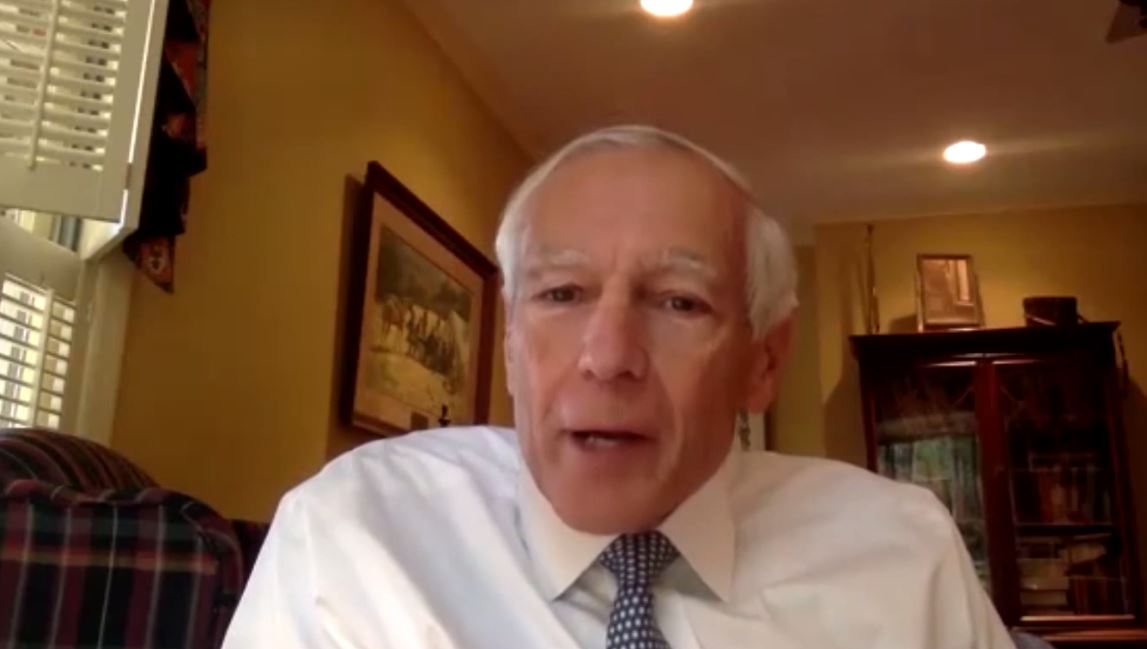

Retired U.S. Army general Wesley Clark, who took part in the peace negotiations that ended the 1992-95 war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, told N1 that if Joe Biden becomes the next president, the U.S. will pay more attention to allies in Europe.

“I think you’ll see strong leadership again, and a greater focus on Europe, and on American friends and allies in Europe,” Clark said, in case Biden comes out as the winner of the US Presidential election.

But that is not to say that Bosnia should expect Biden will solve all of its problems, he noted.

“This has been one of the issues always in Bosnia, not just from 1995 or 1991, but historically. Bosnia has always been the kind of place where local leaders - they look to someone else,” Clark said. “It’s your country, we can’t do it for you.”

Speaking about how Bosnia progressed since the end of the war, Clark said one has to take into account that the Bosnian population is still traumatized from the conflict and that it will take generations to overcome the fears from the past, but that bringing economic development to the country would make that process easier.

“This was a terrible civil war, and tens of thousands, several hundred thousands were killed, and people lost their homes, their families, their husbands, their children,” said Clark, who served as the military member of a diplomatic negotiating team headed by late assistant Secretary of State Richard Holbrooke.

“These feelings don’t go away. They stay. And it will take many many decades, if we can maintain stability in Bosnia and Herzegovina, for the tensions and frictions to decline,” he said.

But that is not only Bosnia’s problem, he argued.

"In our own country, we’re wrestling today with the American Civil War - 150 years later, people are arguing about statues of people who fought in the Civil War.”

“These are passions that are inherent in human beings. It’s what makes us who we are, but somehow we have to have the better angels of our being help us rise above these frictions, to work together and build communities,” he said, adding that “we can’t live in the past, we have to build for the future.”

What changed in the Balkans since the early 1990s is “the willingness to resort to violence,” he said.

“I think that as long as people have fear, there will be politicians who prey on those fears. And to live in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the 1990s was to live in perpetual fear and insecurity,” Clark said.

Those fears he described as “all too real,” and “shocking to those of us outside, we couldn’t believe what was happening.”

“But to live there must have been a nightmare every day,” he said. “A nightmare of fear, violence and uncertainty, in some cases of starvation, so those fears will be there in a, let’s call it the body politic, for a long time. And it will take another generation of leaders, and maybe another generation after that, to move past those fears.”

According to Clark, what can be done about it is to bring economic development in Bosnia, “to provide jobs, to help people look to the future, so that they don’t have to get an education and then leave, go somewhere else, but can stay in their homeland and be with their families.”

“I think to do that we have to be able to strengthen governments. That’s to say that they have to have the resources to provide services that businesses need and people need - schools, utilities, roads and bridges, high-speed internet, mobile phones, 5G, all these things are part of moving forward in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Because ultimately, if people can move forward from their material conditions, they can overcome the fears of the past to an extent.”

Clark addressed the functionality and setup of Bosnia that was agreed during the peace negotiations that took place in Dayton, Ohio.

Those times were difficult for everybody but “especially for Alija Izetbegovic,” the then President of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

“I will never forget when he said he would not accept Republika Srpska,” said Clark, referring to Bosnia’s Serb-majority semi-autonomous entity.

“He said it’s unjust. And then finally he said, ‘I will accept it, but it is unjust’,” Clark remembered Izetbegovic saying.

Still, the agreement made the fighting stop and that’s the bottom line, he said.

“And, although there have been many political issues since then, and things that I’ve been personally disappointed in, like the return of refugees and the ability of the tri-presidency to really bring consensus and bring the ethnic groups together through this conflict, after this conflict, we also have to be realistic,” and consider the fears that still persist in people, he explained.

But the country’s functionality is “more about the people than it is about the structures.”

“I think the structures, how they perform, is a function of how people think. And it’s true that, because there is a separate Republika Srpska, people there feel comfortable maybe living with prejudices and fears and anxieties. But if you had tried to bring everybody together, 25 years ago, it wouldn’t have worked. There was too much animosity there. It might not even work today.”

“I think that we have to be grateful where we are, we have to work it step by step, compromise by compromise, little steps forward, and we have to encourage the young people, who aren’t scarred by bad memories, to get to know each other and to develop trust among the different communities,” Clark said.

“You’re not killing each other, thank God, you’re able to compete for investments, you have an educational system, young people can socialise together - this is what we fought for. This is what we negotiated for. But ultimately you have to make it work,” he said.

Clark also spoke about NATO integration, arguing that it could bring stability to the region, saying that within the Alliance, "militaries work together, diplomats work together, there’s constant interchanges of ideas on many issues."

“It’s not about going to war, it’s about not having a war. It’s about moving forward peacefully," he said, adding, "we’d love to have Bosnia and Herzegovina be a member” and arguing that it would be also be a positive thing for the people of Republika Srpska.

"It would be difficult because they have been inclined toward, let’s say, ‘pan-Slavism’, from the 19th century. Ok, I understand that, but that's not where the economic opportunities are. The economic opportunities remain greater integration with Europe. And I think NATO would facilitate that,” Clark argued.

There are many countries that influence politics in Bosnia and according to Clark, “the real danger is that these countries can use not just military threats but economic power to sway our politics.”

“So I see the most important thing being that people have financial disclosures when they’re in office,” he said. “That you know where they’re getting their money from.”

He stressed that conflict of interest lowers people’s trust in the institutions.

Clark said that “there is no way to know” how much Trump would be engaged in the Balkans if he would stay president, calling him “unpredictable.”

But he stressed that if Trump remains in office, “I think that NATO will be in jeopardy.”

The full interview can be seen in the video above.

Kakvo je tvoje mišljenje o ovome?

Učestvuj u diskusiji ili pročitaj komentare

Srbija

Srbija

Hrvatska

Hrvatska

Slovenija

Slovenija