The "Sniper Alley Photo" project, launched by Dzemil Hodzic, aims to locate and archive photographs taken during the Sarajevo siege (1992–1995). As part of this initiative, the series “The Story Behind the Photo” features foreign photojournalists recounting the stories behind their images from the siege. The first episode of the series' second season focuses on photographer and anthropologist Staffan Löfving and his photograph of two young girls in wartime Sarajevo.

Staffan Löfving, who worked as a freelance journalist in his native Sweden during the 1990s, travelled extensively to Asia and Latin America before visiting Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1993. His first destination was Mostar, followed by Sarajevo in 1994.

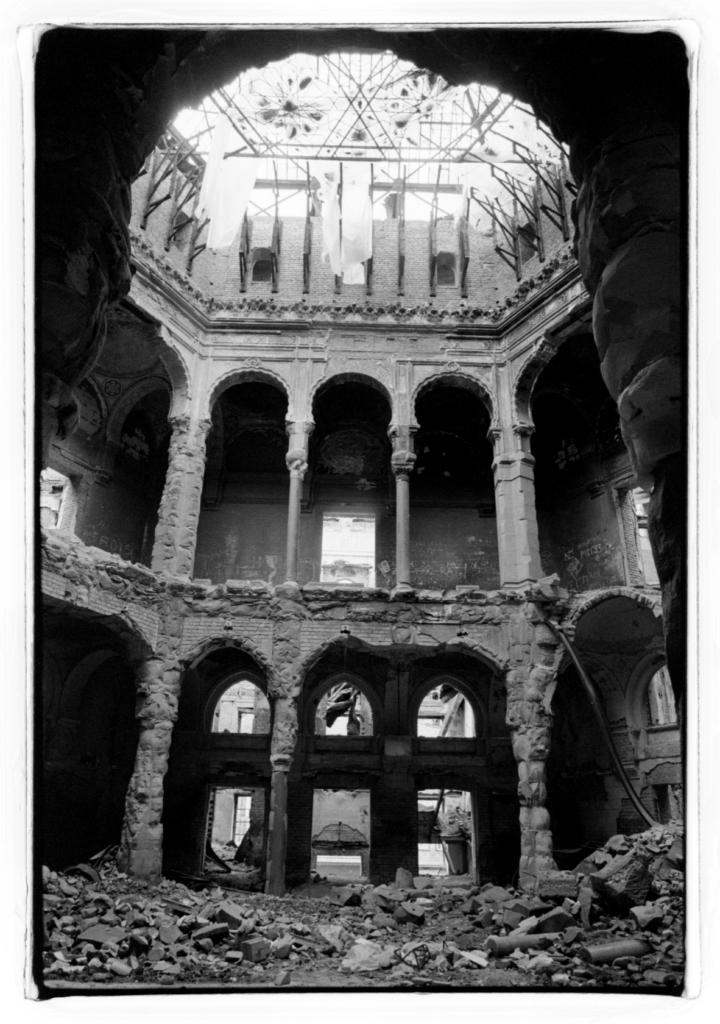

"It was September 1994. I stayed in Sarajevo for about three weeks. Although the war was ongoing, and we experienced shelling and sniper fire, it was not as intense during that period. We stayed with a couple whose daughter we had met in Sweden. She connected us with her parents, who took excellent care of us. Through them, we saw how ordinary people lived during the siege," Löfving told N1.

Already interested in anthropology, a field in which he now works professionally, Löfving sought to avoid conventional wartime narratives from the frontlines, instead documenting the challenges of daily life.

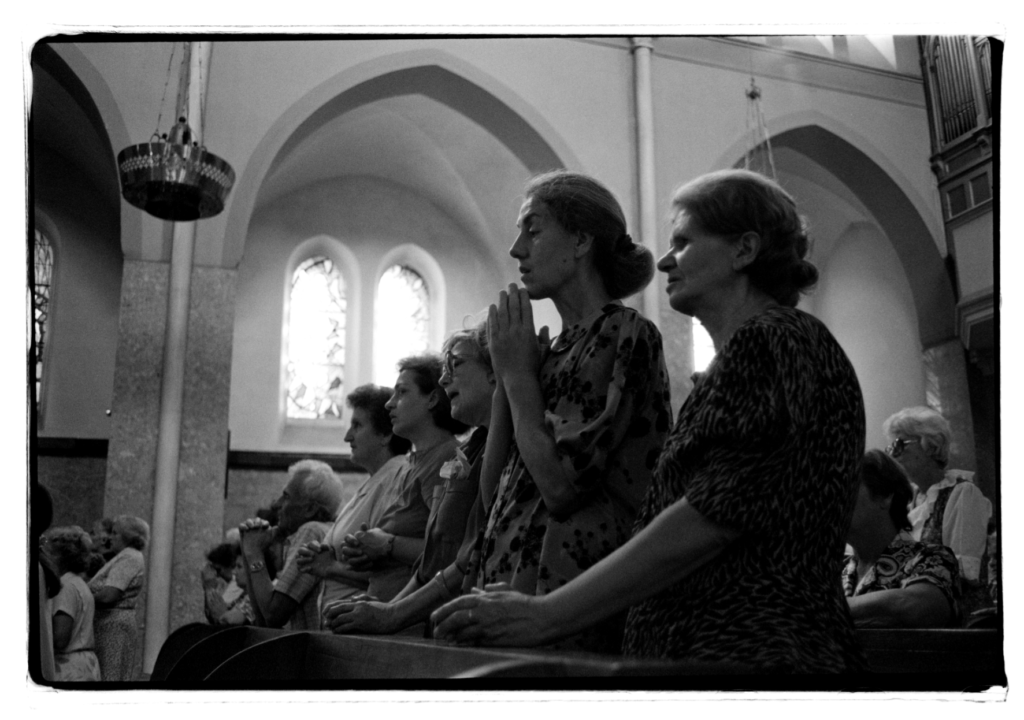

"Our hosts took us to mosques, churches, and hospitals and introduced us to their friends. I carefully documented it all. It took nearly 20 years for me to return to Sarajevo with my photographs to uncover details I had forgotten or not understood during my brief stay. Thanks to these photos, I could continue not just reporting, but some form of anthropological research," Löfving explained.

"Staffan's photo unearthed deeply buried emotions in me"

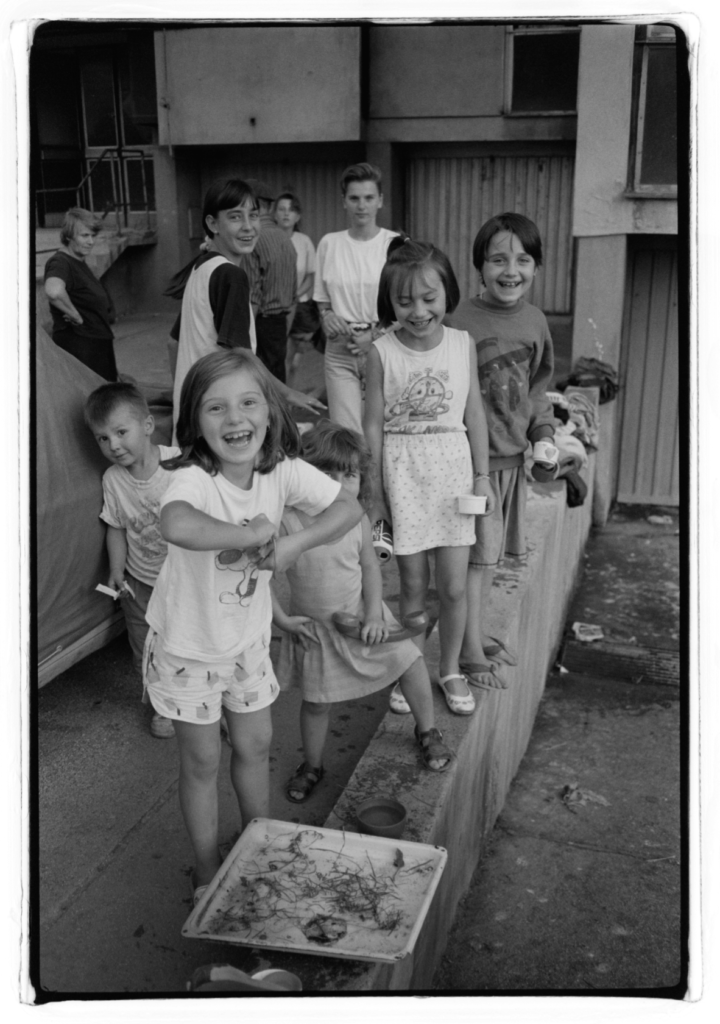

The unique nature of the “Sniper Alley Photo” project is epitomized by a wartime photograph taken by Löfving in 1994, depicting two young girls in Sarajevo's Hrasno neighbourhood. Over the years, Löfving had forgotten about the image and did not know the girls' names. The story took an unexpected turn when one of the girls, Tijana Kolakovic, saw the photograph on the project's Facebook profile.

"My sister sent me a link to the photo and said it was me. I spent a lot of time at Trg Heroja because my grandmother lived there, so it wasn’t impossible that it was me. I vaguely remembered the other girl in the photo, Soraja, but I hadn’t seen her since then. As happy as I was, the photo also stirred emotions I may have buried because we moved to Australia in 1998. I had left the war years behind me and didn’t even want to talk about them," Tijana told N1.

Through Dzemil Hodzic, Löfving learned that one of the girls had been identified. When he travelled to Sarajevo, he contacted Tijana, and together they revisited the location where the photograph was taken.

"He took another photo of me in the same spot, which felt strange and unusual, but the meeting was very pleasant. Staffan is a wonderful person. It felt like we’d known each other for years. We sat and talked about the war, the post-war period, where I’d been, and what I’d done. We’re still in touch and occasionally check in with each other," Tijana said.

"Sniper Alley Photo adds a human dimension to our past"

Tijana attempted to find Soraja Zagic through social media and discovered that her best friend had studied with her. Soraja said that without the photograph, she wouldn’t have known Tijana’s identity.

"A friend sent me the photo and asked if it was me. I initially said no. At first, it didn’t occur to me that it was a photo of me. A few days later, Dzemil sent me the image, and I realized it was me. I don’t know why I didn’t recognize it immediately," Soraja recounted.

Finding the photograph triggered strong emotions for both women in distinct ways. While Tijana had tried for years to leave the war behind, her sister encouraged her to preserve the memory.

"It’s not that I wasn’t interested, but growing up abroad makes you distance yourself from it all. When I got the photo, I thought I didn’t want to be part of this—it was a completely different life that I had left behind. But as time passes, and as I follow everything the Sniper Alley project does, I see how important it is to preserve these memories and not forget them. This photo means so much to me now. I’ve printed and framed it because it’s part of my childhood and has shaped who I am today," Tijana said.

For Soraja, the photograph brought joy as it offered a rare glimpse into her childhood during the war.

"It’s a sweet reminder of my childhood—innocent and naive. It’s also a preservation of our heritage. Dzemil is doing phenomenal work that’s crucial to the city’s history but in a subtle way. He even sent me other photos from Sarajevo with children from that neighborhood, though I couldn’t recognize anyone. Still, I’m always happy to compare the places and wonder who might be in the images. The Sniper Alley project adds a human dimension to our past," Soraja concluded.

"I didn’t enjoy my role in Sarajevo, but Tijana and Soraja’s story changed my perspective"

Löfving praised the beauty of the project and Hodzic's work, marvelling at how the photographs continue to generate memories, stories, and connections.

"It’s amazing that these two girls, now women, reconnected after so many years. It’s fascinating how Dzemil’s project keeps memories alive. This process never stops," Löfving remarked.

After Sarajevo, Löfving moved to Guatemala and pursued long-term work in anthropology. Although he carried his camera, he gradually stopped using it.

"It sank deeper and deeper into my backpack, and I just carried it around. The camera interrupts conversations—if I ask to take a photo, the conversation changes radically, which I didn’t like as an anthropologist. I preferred talking to people without the camera interfering," he reflected.

Regarding the role of foreign journalists during the siege, Löfving admitted dissatisfaction with his part.

"The international media couldn’t significantly influence the situation. Everyone was aware of this and criticized the presence of foreign reporters. We were seen as predators profiting from others’ suffering. I agreed with that criticism and didn’t like my role. But I’m fascinated by Tijana and Soraja’s story because it’s not just a photograph. Behind the image lies so much. The Sniper Alley Photo project respectfully returns wartime photographs to the victims. They used to belong to the media, but now Dzemil is reclaiming them, and I think what he’s doing is incredibly powerful," Löfving concluded.

Löfving calls his Sarajevo photographs “Imperfect Shots,” a term with dual meanings: "imperfect images" or "imperfect (gun) shots." For more about Löfving’s work, experiences, and the “Sniper Alley Photo” project, watch the new episode of “The Story Behind the Photo”.

The team working on the film was the same as in the first season. The production was led by Anna Prokou and Dimitris Sideridis, with Emir Jordamovic as the director of photography, Linus Bergman in charge of sound design, Athar Saeed composed the music, and Kishore Kanchan handled colour correction, along with many other collaborators. For the new season, the Sniper Ally team changed the opening sequence, which was created by the French artist and art director Héloïse Dorsan-Rachet.

Written by Amila Mrkonja.

Kakvo je tvoje mišljenje o ovome?

Učestvuj u diskusiji ili pročitaj komentare

Srbija

Srbija

Hrvatska

Hrvatska

Slovenija

Slovenija