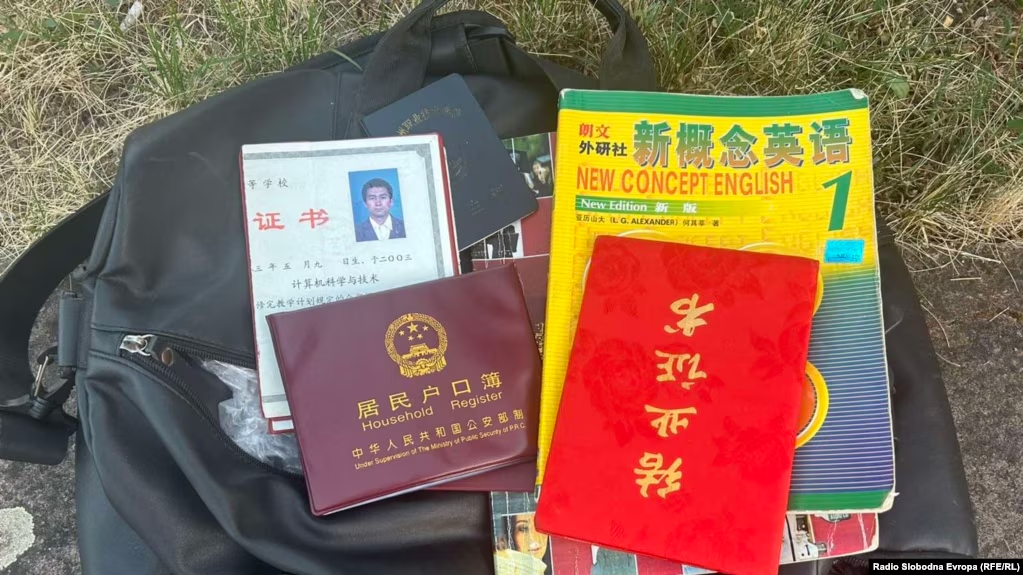

A black travel bag, several Chinese documents, English language materials, and diplomas were all that remained in a Sarajevo hostel after the death of Ehmetjan Ehet, a 42-year-old Uyghur and former witness to China’s detention camps for its Muslim minority.

Ehet, who passed away two months ago at the Sarajevo University Clinical Centre, has yet to be buried. His body remains in a city morgue amid diplomatic complications and what Uyghur activists claim is obstruction by the Chinese government.

According to activists and close friends, Chinese authorities have delayed taking responsibility for the body and have not allowed Uyghur organisations to claim it for a proper Islamic burial.

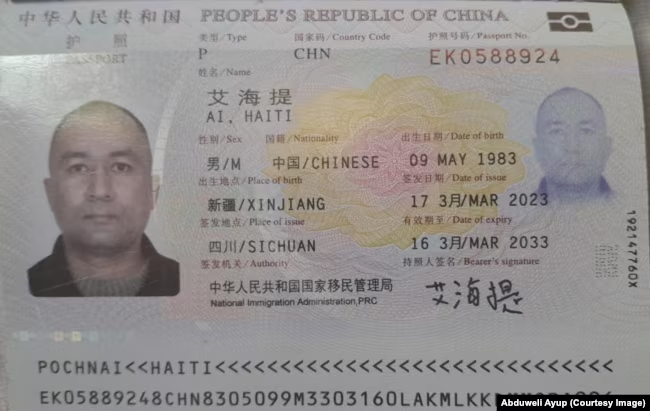

In response to inquiries, the Chinese Embassy in Sarajevo confirmed that “Mr. Ai Haiti died of illness in Sarajevo,” using Ehet’s Chinese-registered name. “The Embassy contacted his family as soon as possible and is assisting in resolving the matter appropriately,” the statement added, without addressing the prolonged delay.

Ehet was a former teacher and prison guard in internment camps for Uyghurs in Xinjiang between 2016 and 2021. His friend and fellow activist Abduweli Ayup, who first publicised the death on social media, described Ehet’s journey from a system enforcer to a witness seeking freedom and asylum.

China’s 2014 “Strike Hard Campaign” in Xinjiang led to the creation of mass internment camps for Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims. Reports from survivors cite forced labour, political indoctrination, family separation, birth control mandates, and restrictions on religious practice.

Ayup said Ehet was coerced into working in two such camps and also served as an auxiliary police officer, a role created by the Chinese government in response to mass arrests. Despite the personal risks, Ehet gradually shared details of his experience with Ayup, who documents the stories of Uyghur escapees.

Ehet managed to leave China in 2023, travelling through Uzbekistan to Turkey after receiving a passport in Chengdu. He changed his name and adapted his identity in hopes of escaping government scrutiny.

“He told me he just wanted to live somewhere without the shadow of the Chinese Communist Party,” Ayup said. “But even in death, he’s not free from their reach.”

In November 2023, Ehet testified, partially and anonymously, at a Uyghur human rights hearing in the Czech Parliament. Fearing for the safety of his family still in China, he refused to be recorded or identified. He later applied for asylum in the Czech Republic, which was denied, prompting his return to Turkey.

In April 2025, Ehet travelled to Bosnia and Herzegovina, telling Ayup he hoped to seek asylum in another European country. A few weeks later, on May 31, Ayup received a call from someone who said Ehet had died. The information came from a fellow hostel guest who had accompanied him to the hospital in Sarajevo after his health deteriorated.

A representative from the hostel told Radio Free Europe that Ehet had appeared ill upon arrival and grew weaker over time. A Chinese Muslim guest eventually took him to the hospital. Later, the same man called to report Ehet’s death.

A bag left behind contained personal belongings and banknotes from an unnamed African country. Ayup confirmed that Ehet had worked in Africa for several months before arriving in Bosnia.

Although doctors at the Sarajevo Clinical Center suspect malaria as the cause of death, no official medical report has been released.

The World Uyghur Congress, based in Munich, attempted to claim Ehet’s body via a partner humanitarian group in Sarajevo but was denied. Chinese authorities insisted they would manage the process, yet the body remains unclaimed.

Activists worry that even Ehet’s burial could be manipulated. They point to China’s growing practice of cremating Uyghur dead—contrary to Islamic traditions—as evidence of continued state control over Uyghur customs.

“He wanted peace. He wanted freedom,” Ayup said. “And now, not even death has given him either.”

Kakvo je tvoje mišljenje o ovome?

Učestvuj u diskusiji ili pročitaj komentare

Srbija

Srbija

Hrvatska

Hrvatska

Slovenija

Slovenija