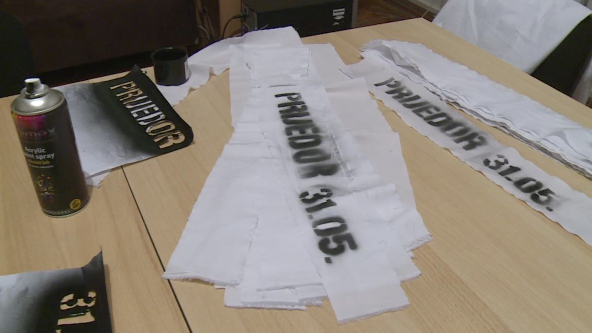

Survivors of the wartime killing of non-Serbs in the northwestern town of Prijedor are commemorating May 31, 1992, the day when they were ordered to put white ribbons on their arms to mark themselves as non-Serbs.

The wartime campaign to eliminate all non Serbs from the Prijedor area took 3,176 lives, mainly at the start of the 1992-1995 war.

The victims include 102 children, and this years’ commemoration will be focused on them.

When Bosnian Serbs took exclusive control of Prijedor in 1992, they ordered the non-Serb population to wear white ribbons around their arms and put white sheets in their windows.

“The white ribbons are one of the things proving the intention to commit a genocide in Prijedor, as the group was marked in a visible and clear way for extermination and expulsion from that territory,” former inmate at the Omarska, Manjaca and Trnopolje concentration camps, Mirsad Duratovic, told the Fena news agency.

The portions militarily controlled by Bosnian Serb forces remained part of Bosnia but were turned into a semi-autonomous entity called Republika Srpska. Prijedor is now in Republika Srpska and non-Serbs who survived the ethnic cleansing and returned to Prijedor are focusing this year’s commemoration on their attempts to build a monument to the children killed in town, an idea the Serb city authorities reject.

“White ribbon day” will also be marked in Serbia’s capital, Belgrade, by the ‘Women in Black’, an NGO promoting peace and reconciliation.

Several wartime Serb soldiers and police officers who committed the crimes in Prijedor were sentenced to a total of 770 years behind bars, in 51 final instance verdicts.

“Those verdicts are aimed at Prijedor’s Serb nationalist citizens, and there is not a city in the world where that many of its citizens were sentenced for war crimes committed against their neighbors,” Duratovic said.

He added that there are still 37 ongoing trials at the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and expressed hope that the perpetrators will be held accountable for those crimes.

“Today in Prijedor you don’t live, you survive, as we are a ‘foreign body’ which someone tried to get rid of in 1992, and they didn’t manage to do that with the genocidal operation, so today they are doing that with other, but not any milder methods which are not as visible as genocide,” Duratovic said.

He said this is portrayed by thousands of discrimination cases endured by those who returned to the area, former concentration camp inmates and victims of war crimes, who are deprived of basic rights.

Duratovic said that he, as a former concentration camp inmate, is not recognised by the system in place in the RS.

“On the contrary, the legal solutions and rules openly, without any attempt of hiding it, prefer members of the military units of the RS. When the city provides stipends from its budget, in the rule book it states that children of war veterans and those disabled from the war have an advantage, while children of former concentration camp inmates don’t even exist (in the system),” he said.

Nothing in Prijedor reminds of those thousands of citizens that were killed, Duratovic said, as there is not even a small sign on the buildings that were formerly used as concentration camps or in the vicinity of mass graves.

But what can be found are signs and monuments with photos and names of former workers in companies and institutions who were members of the former RS Armed Forces and who died on the front lines somewhere during the war.

For members of ethnic groups other than Serbs, there is nothing of that sort.

“In the Trnopolje concentration camp, there is a monument to fallen members of the RS Armed Forces, and in the rooms where inmates where being killed and where women and girls were being raped, there are photos of fallen soldiers who are not from Trnopolje. It was important to mark the territory,” Duratovic said.

The former inmate said this was a clear message to returnees that they are not welcome in Prijedor, where the authorities are using every opportunity to “silence the voices” of those who speak the truth.

“Those who ‘survived’ Prijedor still think a genocide took place. Why don’t we have the right to call what happened to us by it’s real name, and not how someone determined it?” Duratovic asked.

For him, it is hypocritical for Serbs to say that there is not one official ruling determining that there was a genocide in Prijedor, while at the same time they are commemorating crimes committed against Serbs in Jasenovac and Kozara during World War II, for which there are also no official rulings.

“What the international community and human rights organisations didn’t consider is the fact that, at a 2012 session, the City Assembly in Prijedor banned the financing of all organisations that deal with the Prijedor genocide,” Duratovic said, adding this ban is still in place.

He said the international community is trying to create conditions for the return of those who were expelled, but that is is not reacting to the “silencing of free speech”.

Duratovic said that citizens who are subject to discrimination can endure this for a few years, but after some 15 or 20 years, they simply give up because of the pressure, mostly in fear of losing employment.

On July 20, 1992, Duratovic lost his father, brother, grandfather, uncles and cousins and many other family members – 47 of them in total. He was a boy who was used as a living shield, and he only survived due to luck. After that, he was taken to Omarska, then to Manjaca, and then to Trnopolje.

Kakvo je tvoje mišljenje o ovome?

Učestvuj u diskusiji ili pročitaj komentare

Srbija

Srbija

Hrvatska

Hrvatska

Slovenija

Slovenija